3 fundamental user onboarding lessons from classic Nintendo games

.png)

.png)

Editor's note: This article was originally published in 2016 and updated in February 2020.

Game developers in the 1980s didn’t just need to teach people how to play the games they made—they needed to teach people how to play video games, period. For many, the classic Nintendo games of the ’80s were the first games they ever played, and the moment they first fell in love with gaming.

The very existence of the burgeoning video game industry depended on the games being both entertaining and easy to learn. That’s why user onboarding in early games was so essential.

In many cases, an effective user onboarding strategy meant the difference between a beloved classic and a forgotten flop.

Today, many of those same time-tested strategies are used by developers to create more delightful user experiences and help new users achieve value from their apps—for everything from mobile gaming to SaaS products. This use of gaming mechanics and experience design in non-gaming products is called gamification and is used to motivate users to complete tasks and boost engagement.

In this article, we’ll take a close look at 3 critical lessons about user onboarding that you can learn from classic Nintendo games, along with how to use these strategies to level up your own desktop or mobile app.

Gamification has been a buzzword for years now, and chances are you’ve got a general understanding of what it is. But a strict definition can be tricky to nail down—everyone seems to have their own way of defining gamification.

Part of the problem is that there are actually 2 types of gamification: structural gamification (aka game mechanics) and content gamification (experience design).

Karl Kapp, an expert on gamification in e-learning, explains:

[Structural gamification] is the application of game elements to propel a learner through content with no alteration or changes to the content itself... The primary focus behind this type of gamification is to motivate the learner to go through the content and to engage them in the process of learning through rewards...

[Content gamification] is the application of game elements and game thinking to alter content to make it more game-like. For example, adding story elements … or starting a course with a challenge instead of a list of objectives are both methods of content gamification.

Put more simply: Gamification is the application of game elements to non-gaming environments to motivate users and make tasks more enjoyable.

David Teodorescu, senior product designer at Fitbit, lists 7 key components for gamification:

Now that we’ve reviewed what gamification is, let’s take a closer look at where some of those game elements come from. Specifically, we’re going to look at how a handful of early Nintendo games onboarded new users—for good and bad—and how you can apply the lessons from successful Nintendo classics to your own app through strategic gamification.

Super Mario Bros., released for Nintendo Entertainment System in 1985, opens with World 1-1—perhaps one of the most iconic video game levels of all time. It’s also a master class in user onboarding, explaining how to play the game through gameplay itself.

Legendary game designer and creator of Super Mario Brothers Shigeru Miyamoto explained that the goal of World 1-1 was that “within that one section…the player would understand the concept of what Mario was supposed to be and what the game was about.”

The level starts with a menacing Goomba (a sentient mushroom) moving towards Mario (pictured above). It turns out that the Goomba was actually a late addition.

Originally, the designers started players off with an altercation with a Koopa Troopa (tortoise-like critter). You may remember that defeating a Koopa Troopa was a 2-step process: (1) stomp on them and they’ll go into their shell, and then (2) kick the shell. After thinking about it, designers decided that a multi-step process might be too complex for a first-time enemy encounter.

Miyamoto and team explicitly invented the Goomba as an enemy that you could defeat with a jump alone.

Later in 1-1, the game designers prepared players for the more advanced concept of the B-Dash—wherein you could hold down the B button to run. They created two nearly-identical formations with gaps in between that would inspire you to build up speed to jump across. If you fell into the first gap, you would land safely, but falling into the second gap would kill you.

As Miyamoto describes it: “We added a hole that you’ll need to speed up for and then jump. [However,] we made sure that there were some parts that even if the player fell, it would be safe. By doing that, we wanted the player to gradually and naturally understand what they’re doing.”

This progressive onboarding technique is sometimes called instructional scaffolding and is used to teach users progressively more difficult skills by building on previous experiences.

According to Miyamoto, it’s incredibly powerful to teach a player how to play the game in the game, because that way they quickly take ownership over what happens. While walkthroughs or tours can explain how a product works, interactive tutorials and learn-by-doing onboarding experiences get users actually doing the thing that they need to do to achieve value. “Once the player realizes what they need to do, it becomes their game,” Miyamoto emphasized.

Watch Miyamoto explain the thinking behind the design of World 1-1 in full:

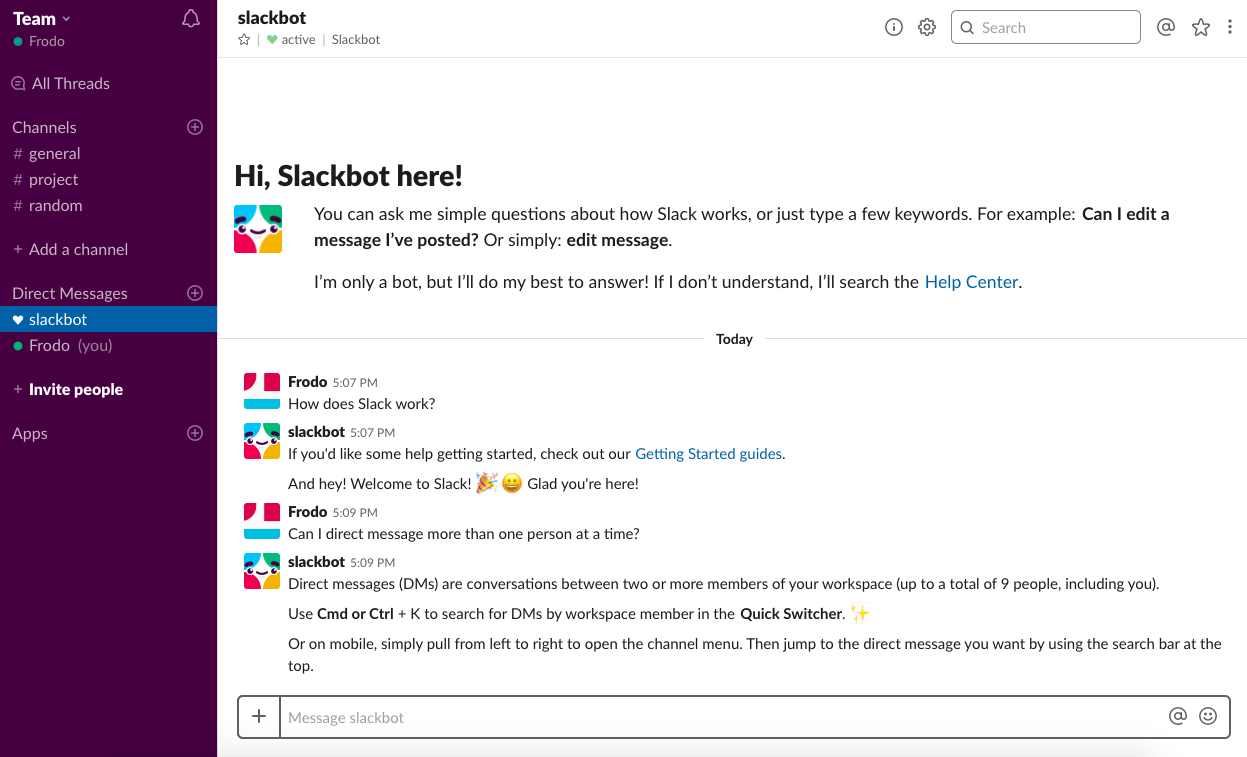

Slack onboards new users by getting them to jump right in and chat right away—with a computer named Slackbot. As Benjamin Brandall of checklist software app Process Street points out, chatting with Slackbot demonstrates:

“We think we’re chatting to a nice, friendly robot when we’re actually learning things,” Brandall observes.

Grammarly introduces new users to their grammar checking tool with an interactive demo document that’s packed with feature demonstrations. Users learn how to edit documents and familiarize themselves with the Grammarly assistant by performing actions and making edits that they’re likely to encounter in their own projects. It’s a simple but powerful example of learn-by-doing that teaches new users about the Grammarly interface, while showing off the product’s capabilities.

In Contra, released for NES in 1987, you had to get through 8 stages of insanely difficult guerrilla warfare wherein touching a single bullet was enough to kill you—with a total of just 12 lives to space. Yes, the game offered freedom to fail—but just barely. That’s why Contra is often recognized as one of the most difficult games ever made.

In fact, many classic Nintendo games were absurdly difficult. When games today are built to evoke a retro feel, they’re often purposely designed to be hard—but that wasn’t a conscious decision for game designers in the ‘80s.

Former Nintendo president Satoru Iwata, explains that games ended up being so difficult as a result of a quirk in the game development process. And it’s something that plagues product teams of all kinds to this very day:

Video games from that era are abnormally hard. Back in the NES generation, for example, let’s say everyone debugs a game after it’s finished. Everyone involved in the production would spend all night playing it, and because they made games, they became good at them. So these expert gamers made the games.

When you build a product, you become an expert in that product—and that can blind you to the difficulties that a naive user may have getting started or performing the same tasks that you find so simple. It’s easy to confuse your knowledge and experience with intuitive design.

Take a cue from Iwata’s reflection on game development: Design your user onboarding for the naive user, not for the product expert.

When HubSpot redesigned its new user onboarding flow, it extensively incorporated user testing sessions with real users into the process—and it was able to 4x its target metric as a result.

Rather than just run user testing internally with an in-house UX or QA team, it reached out to people outside of the organization, talking directly to unengaged trial users—naive users for whom the current new user onboarding flow had failed.

At each step of the user testing process, former HubSpot UX researcher Rachel Decker (now PM at ezCater) placed extreme importance on making users feel comfortable to make mistakes and tell researchers where they were getting tripped up. It’s exactly those stumbling blocks that you’re likely to overlook as an expert in your own product—and where you’re most likely to find your opportunities for meaningful improvements.

We’re big on user testing here at Appcues. And we believe that every engineer should get involved in the user testing process to build the empathy they need to create truly exceptional product experiences.

For more user testing tips, check out 6 Tips to Make User Testing a Breeze.

The “need to complete” is one of the most powerful psychological drivers of video game engagement, and no classic game embodies that better than Tetris (released for NES and Game Boy in 1989).

In Tetris, puzzle pieces fall from the sky—organize them neatly to create complete horizontal lines, and the blocks will disappear. Otherwise, the blocks stack up until they fill up the screen, and then it’s game over. What sounds like a very simple mechanic actually becomes incredibly addictive as a result of a psychological phenomenon known as the Zeigarnik Effect.

Back in the 1930s, Russian psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik observed that waiters had amazing abilities to remember a large number of complex orders. But once the order had been fulfilled, something interesting happened: The waiters instantly forgot what it was that customers had ordered as soon as the food and drink hit the table.

Zeigarnik found that while uncompleted tasks stick in a person’s memory, completed tasks are more easily forgotten. When you pursue a task but leave it unfinished, your brain will keep bugging you about it until it’s done.

“Tetris does this wonderfully…[because] it presents a world of perpetual uncompleted tasks,” says to Tom Stafford, psychologist at the University of Sheffield. You get totally hooked as completed tasks disappear and they’re instantly replaced with more incomplete tasks.

Many modern game and app developers have taken this lesson and applied it to the very earliest stages of the user journey, where it’s most critical that you hook the user on your product—user onboarding.

Blogging platform Ghost noticed that when a user added a custom theme during the onboarding process, they were 1,000% more likely to convert to paying customers. That was a massive insight, which prompted the question: How do we get more users to add a custom theme?

In 2014, Ghost added a simple progress bar to its onboarding flow. There were 5 steps, one of which was to replace the default theme with a theme of their own choice. This simple design choice gave users a sense ownership over their blogs..

Completing each step would add a bit more orange to your progress meter, until it was all filled up. Each incomplete step was reinforced with the negative space in the progress meter, a checklist of remaining steps, and email reminders that would get triggered when users hadn’t signed in for a couple of days.

The results speak for themselves: Prior to creating the progress bar, only 7% of users had added a custom theme during their trial period. After they added the progress bar, that number jumped to 26%, a nearly 4x increase of trial users primed to buy a full paying subscription.

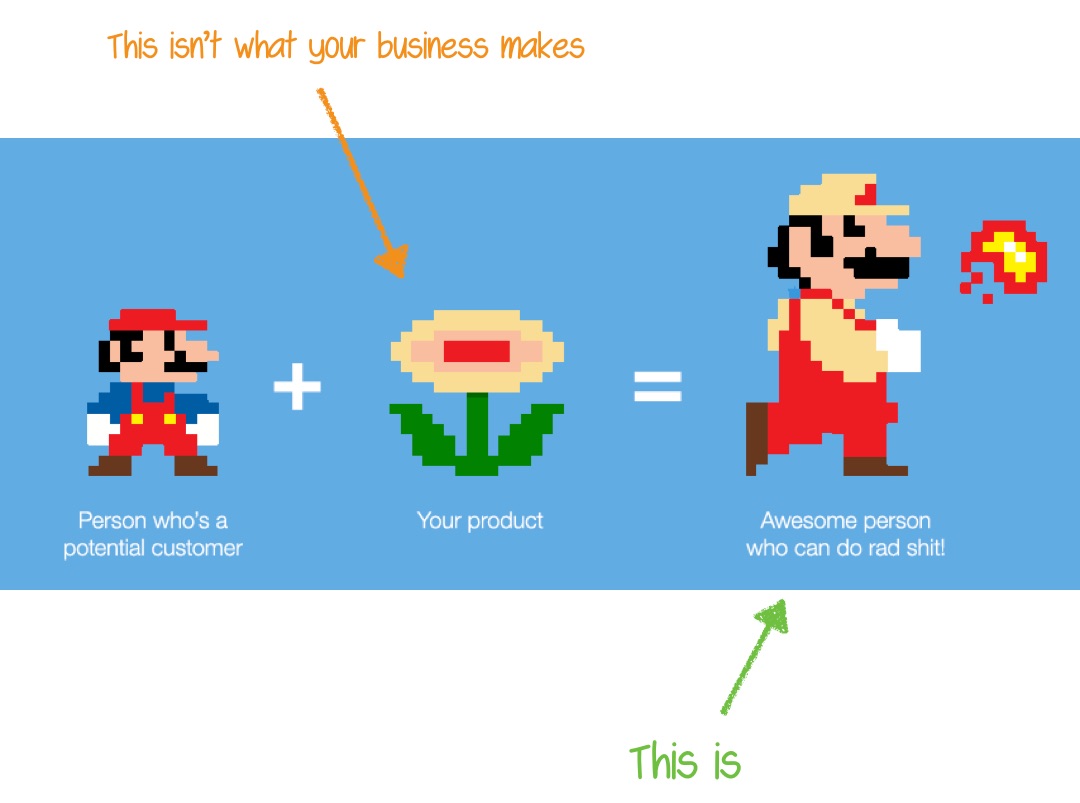

Samuel Hulick of UserOnboard is often quoted as saying that:

People don’t buy products; they buy better versions of themselves.

In other words, they buy your product to go from small Mario to fire Mario. Your onboarding experience is, essentially, when they learn to use their newfound powers. Do it right, and your users will be saving the Mushroom Kingdom in no time.